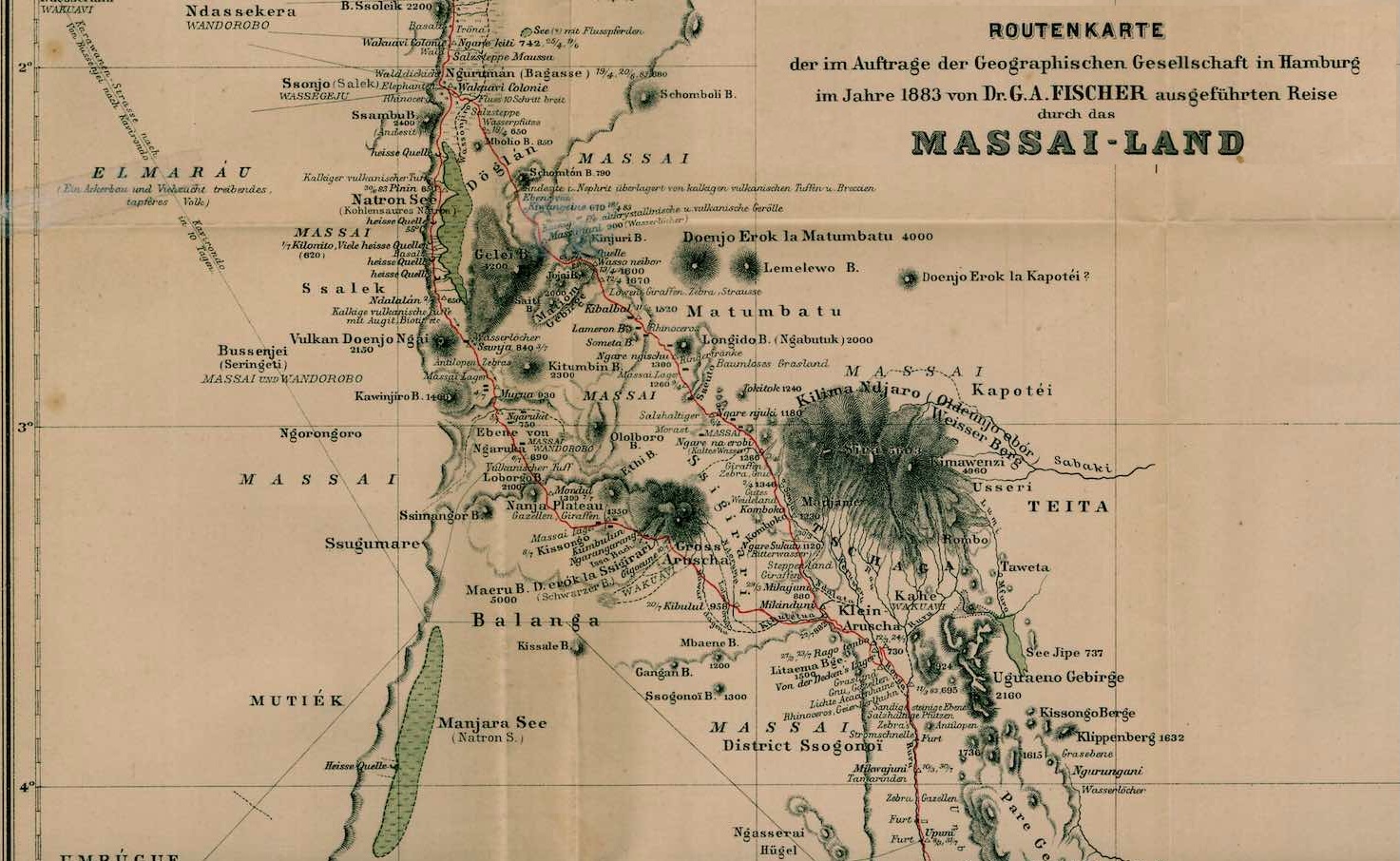

Here is another translation of a rare traveler’s account of the interior of pre-colonial East Africa: the 1882-3 expedition of the naturalist Gustav Fischer, who ventured inland from Pangai (in today’s Tanzania) all the way to Lake Naivasha (in today’s Kenya), traveling through uncharted Maasailand some months before the more well-known expedition of Joseph Thomson.

Fischer’s article (link here) was published in German as “Report of the Journey into Massailand, taken under commission for the Geographical Society in Hamburg” in the journal Mittheilungen der Geographischen Gesellschaft in Hamburg (Transactions of the Geographical Society in Hamburg), 1882-83. Fischer begins by describing the logistics of setting up an expedition, including the exasperating business of recruiting labor. As he proceeds on his route, he describes the various items used for bartering, tribute payments, and (in one case) blood money. He reports on the varied flora, fauna, terrain, and geology of the landscapes he passes through, as well as meteorological observations and the fertility (or lack thereof) of the land.

Fischer’s route goes up the Pangani River, skirts the Usambara and Pare mountains, past Mount Kilimanjaro (whose snows he describes as seen from a distance) and Mount Meru, past Lake Natron, and north along the foothills of Nguruman. He reaches as far north as Lake Naivasha and the hydrothermally active area of hot springs and steam vents around it, before being forced to turn back by an increasingly hostile band of warriors.

Along the way, Fischer relates a number of anecdotes of his firsthand interactions with the Maasai, including their boisterous amusement at his appearance, and two harrowing attempted attacks on his caravan. He provides secondhand descriptions of other Maasai raids and the Mbatián, the most powerful and affluent individual among the Maasai. The article includes descriptions of Maasai huts and encampments, clothing, ornamentation, ethnic complexions, livestock, the Maasai diet and mores surrounding it, the divisions of roles between men and women, the different classes among Maasai men, their beliefs in supernatural powers, their rites, and the rough concept of the divine “Ngai.”

Fischer also includes descriptions of other tribes, such as the Waruvu and Wandorobo, and especially the Wakwavi, and their cultural, geographic, and adversarial relations with each other. The Wakwavi are described as a once-powerful tribe living in areas now dominated by the Maasai, with whom they have integrated to varying degrees.

A few photographs appear in the text, and an appendix includes drawings and descriptions of ethnological artifacts.